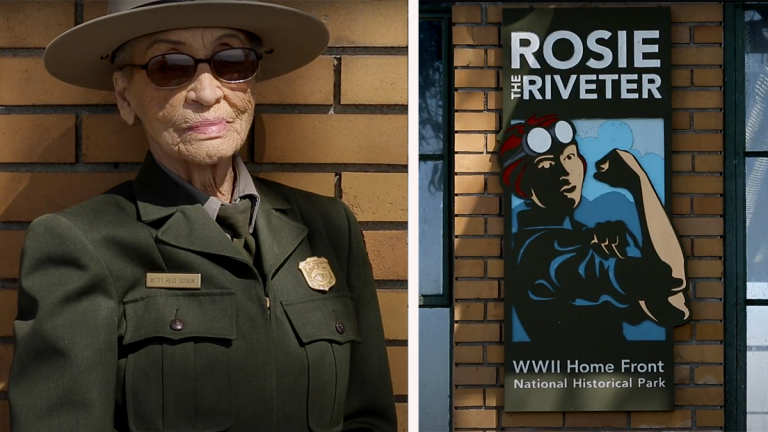

Since 2004, Betty Reid Soskin, 99, has been working at the Rosie The Riveter World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California. Today, she’s the oldest park ranger in America.

On popular bus tours, Soskin tells visitors first-hand stories about her earlier days as a 20-year-old African American in the Richmond shipyards during World War II. During the early 40s, she worked as a file clerk in a segregated union hall.

Today, the pandemic forced the park to temporarily close. However, October 24, 2020, marked the 20th anniversary. In her 70s, Soskin personally took part in the early planning of the park. At early meetings, she was the only person of color in the room.

Related Read: Heartwarming Reason 94-Year-Old WWII Vet Stands Outside Middle School Every Day

A Park Ranger at Age 85

By age 85, she unexpectedly became a park ranger at the park she helped design.

“My fingerprints are all over this park,” Soskin recalls.

The historic park on the San Francisco Bay is the flagship site telling the untold story of Rosie the Riveter.

Today, the popular image of Rosie, flexing her muscle with the caption, “We Can Do It!” is forever a part of American culture. In 1942, it was a popular song praising female assembly-line workers, an optimistic rallying cry.

Rosie the Riveter and Segregation

As Soskin remembers, Rosie the Riveter was always depicted as white due to segregation.

“Rosie, the Riveter was a white woman’s story,” Soskin tells visitors. “There were no black Rosies. Segregation still prevailed in California in the 1940s, and blacks were forced to work menial jobs.”

During World War II, Richmond was a boomtown as 100,000 people migrated overnight to the city to support the war effort. Suddenly, the bay was home to 56 different war industries, including bomb production and homebuilding.

In Richmond, thousands of women and men worked together to build some 747 ships at record speed between 1940 and 1945. It was more ships than any other shipyard in America.

According to History.net:

“… Richmond’s women workers weren’t in fact riveters, since Kaiser’s new method of ship construction used welding over riveting. They were really “Wendy the Welders,” along with machinists, drivers, shipfitters, electricians, carpenters, and all kinds of other workers.”

At the time of segregation, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser hired African American workers from the South for low-level positions. Employees enjoyed rare social support programs for workers, such as childcare and pre-paid health plans.

See more about Betty Reid Soskin from the San Francisco Chronicle below:

Today, at 99, Soskin is proud to wear the U.S. park ranger uniform, knowing that every time a young person of color sees her, she is silently sending them an empowering message.

“I’m announcing silently to every child of color a career path that they may not ever be aware of because they’ve never seen a person of color like me in a National Park uniform,” she says.

Originally, the planners designed the park as an homage to the women who worked on the homefront. Thanks in part to Soskin, it honors the complete story.

Telling the Untold History

In her recent Newsweek article, Soskin writes:

“The Rosie the Riveter park was originally planned as an homage to the women who had worked on the home front, and it was situated in Richmond because of the enormous war effort that mobilized there, including four Kaiser Shipyards, during World War II.”

“But the park eventually became much more than that, because it was clear that women of color were involved in many of the aspects of the home front. It was not that the park planners had an approach that was wrong, it was just that the story was incomplete without my part of it. Because the story as I was telling it had not existed before.”

Following the war, African Americans were the first to lose their jobs and benefits after the war. The building where Soskin had worked as a clerk was torn down immediately. With no records left of it ever standing, Soskin tells the missing story.

Still Making History at 99

Today, Soskin tells the stories that might have otherwise been lost forever. On her tours to the scattered park sites, Soskin says people are often astounded by the untold history.

“And as I began to introduce my part of the work, it was very clear that many of the stories of Richmond during the war were not being told. There were other stories, such as of the 120,000 Japanese prisoners that had been interned in America and the Port Chicago disaster which destroyed two ships, and killed 320 people, including 202 African Americans. And these stories have now been incorporated into the park.”

Well past the average retirement age, Betty Reid Soskin started a new career. In 2015, she introduced President Obama at the National Christmas Tree Lighting. By 2018, she published her memoir, Sign My Name to Freedom, a Memoir of a Pioneering Life, and sang with the Oakland Symphony.

Her advice for others who hope to have such a long, incredible life;

“I think that maybe if I could offer any advice, it would be to stay involved. To do anything less than that is to not measure up to one’s potential. Because you never know when you throw the spaghetti against the wall, what’s going to stick. When you’re making history, you have no idea that’s what’s happening. You don’t realize until later,” she said.

Now, although she feels like she’s “done it all,” she’s remains ready for anything.

More about Soskin from Manufacturing Talk Radio below:

Featured image: Screenshots via YouTube